By Ned Rozell

Ice that floats on far-north oceans has been dwindling the last few years. Scientists have described the shrinking of this solar reflector — once bigger than Russia and now taking up less space than Australia — as a breakdown of the world’s refrigerator.

But a group of researchers have found a sliver of good news in the disappearing sea ice off Alaska’s west coast — the ocean floor around Bering Strait still seems to be capturing billions of bits of carbon that might otherwise lead to an even warmer planet.

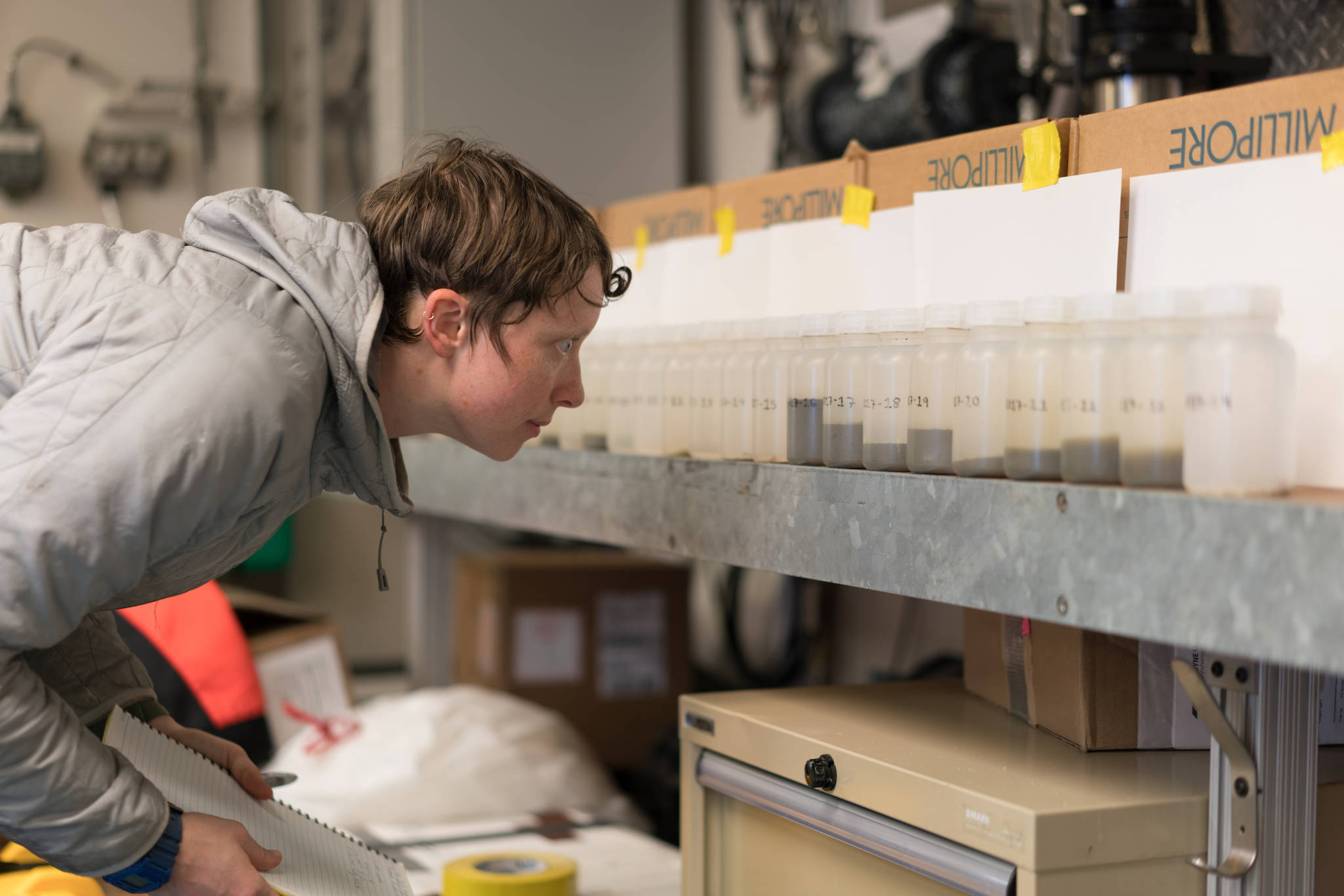

“This could be a region of resilience,” said Steffi O’Daly, a graduate student at the University of Alaska Fairbanks College of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences. She sailed in and around Bering Strait — the narrow passage between Alaska and Russia — a few years ago. Aboard a research ship, she sampled small patches of sea water deep beneath the surface.

Though its absence or presence effects weather all over the globe, northern sea ice is an abstraction for most people. Jigsaw pieces of ice emerge and grow during the polar winter. In recent years, partly because of warmer ocean water, much less sea ice has bobbed on the ocean off the coast of western and northern Alaska, and on the skullcap of the planet — the Arctic Ocean basin.

Though sea ice grows in fall and winter, it shrinks every spring and summer as the planet nods back toward the sun.

O’Daly, an oceanographer getting her Ph.D., said that some scientists think oceans that are less covered with sea ice will further warm the Earth, due to living things in the water.

How? Longer seasons of open water each year might favor organisms like phytoplankton (microscopic, free-drifting plants) and fast-growing animals that eat them. Those hyper little animals create carbon byproducts that exist in several forms near the ocean surface. Stormy seas can liberate that carbon from the ocean into the air.

[Goodbye to a raffish glacier scientist]

But O’Daly found on her June 2018 journey that a majority of the tiny specks of carbon from animal activity were sinking to the bottom, where they could become buried in the sea floor. Those specks include dead and dying phytoplankton, fecal pellets, and dead bodies of zooplankton (tiny snails, krill, worms and other creatures that feed on phytoplankton and themselves are food to many things, including baleen whales).

Seawater is only about 120 feet deep above the Bering Sea’s continental shelf, much of which used to be the plains of the Bering Land Bridge. Scientists discovered long ago that the underwater shelf is where massive amounts of carbon sinks into the muck at the bottom. There, it settles into sediment or feeds the clams, worms and other things that live on the seafloor.

But the ice above the shelf is not what it used to be, with huge swaths of the Bering and Chukchi seas now dark and wavy in winter instead of blue-white.

O’Daly worked from the UAF ship Sikuliaq in June 2018, at a time when people in Alaska villages on the northern sea noticed much less sea ice. They also found the corpses of hundreds of sea birds washed up on their shores. The birds may not have been able to find their favorite plankton or fish species.

Bering Strait waters have been about 3 degrees warmer than the long-term average in recent years, and during the time O’Daly was up there, sea ice was hard to find; in the same area five years earlier, the Sikuliaq would have needed to break through ice.

“We were up there sampling at this time of really, really rapid change,” O’Daly said.

While O’Daly said more studies are needed to supplement her team’s snapshot in time and space, her finding was significant enough to merit a journal article. And maybe it allows a little sigh of relief — at least a small patch of ocean off Alaska still seems to be gobbling up carbon.

• Since the late 1970s, the University of Alaska Fairbanks’ Geophysical Institute has provided this column free in cooperation with the UAF research community. Ned Rozell ned.rozell@alaska.edu is a science writer for the Geophysical Institute.